It is hard to explain how a book begins. Writers have their own vocabularies to make sense of it, sets of metaphors that come close to describing what happens in the authorial brain when a book starts to take shape. When it lights off on a long journey from vague, unconnected ideas to something almost terrifyingly complex, real, and tangible. For some, a book is a child growing within, straining toward birth, for others it is a building painstakingly engineered, for others it is a seed that puts out strange and unpredictable shoots. And for many of us, it is all of those things and none of them, but when an interviewer asks, we have to come up with some image to describe a process that is part puzzle. part translation, and part highwire act, involving not a little bit of sympathetic magic.

In the case of The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making, all my models went out the window. It was a serial novel; chapters appeared every Monday for three months or so in 2009. You can still see the shape of the serial in Fairyland, in the cliffhanger chapter endings and the quick leap into action. Writing a serial in real time takes a certain amount of bravado—you can’t go back and change anything, and yet, if you are lucky enough to engage a week-to-week readerships, your audience will respond to every chapter vociferously, pointing out everything from spelling mistakes to what they hope will happen, what you’ve done wrong and what you’ve done right.

You learn to write a novel all over again every time you write a new one, and that was how I learned to write a Fairyland book: quickly, without fear, and in front of everybody, leaping into the dark and hoping I could land all those triple somersaults.

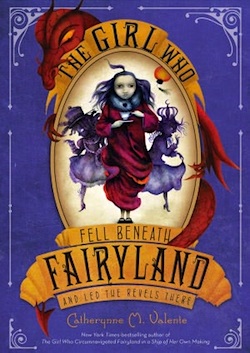

But Fairyland is not a standalone novel. The sequel, The Girl Who Fell Beneath Fairyland and Led the Revels There, comes out this October. And it was not serialized. I wrote it on my little island, by myself, without that time pressure and need to get it right on the first go, but also without that instant feedback and sense of community following September’s adventures. It was strange, new territory, taking Fairyland away from its home country.

But then, fiction is always a headlong bolt into the unknown.

In this case, the book began with an image.

Sometimes it’s a line, sometimes it’s a character, sometimes it’s the end, sometimes it’s the beginning, but the kernel of a novel, the seed of it, tends to roll around my brain for many months, accreting story like a tiny, hopeful Katamari. Long before Fairyland was even released in print form, I had the image of September dancing with her shadow in my head, careening around, looking for a story to carry it.

I did not want to write a sequel that was just a comforting re-tread of September’s adventures. I wanted to change the game, engage the real world in surprising ways, never allow September to get complacent about Fairyland and her place in it. If The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland was a retelling and reimagining of the folklore of classic children’s literature, when I returned to that world I wanted to dive straight into old school mythology and reshuffle the deck.

It was a lonelier process. I couldn’t see whether I had gotten it right or wrong immediately. I held it all in my heart and tried to fit it together into the right shape—which I’ve done for every other novel I’ve ever written. But Fairyland has always been a little different form my other books. On the other hand, I could change things, rearrange them, make the story a bit less episodic and breakneck, more cohesive. Every way of writing has its pluses and minuses; every book is hard.

In some sense, writing a book is like going into the underworld. Every author is Persephone, possessed by a story, compelled to pursue it down into dark and primal spaces.

And that’s just where The Girl who Fell Beneath Fairyland and Led the Revels There goes.

I wanted to write an underworld story—of course, The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland is also an underworld story. All portal fantasies are. The capital of Fairyland is Pandemonium, which is also the capital of Milton’s Hell. Fairies and hell have what we might call a complicated relationship in folklore, allied or opposed depending on the tale. Sometimes the fairies must pay a terrible tithe; sometimes they kidnap human children and drive men to madness. To travel into the world of fairies is always to echo Inanna, Persephone, Theseus, Odysseus. All Fairylands are and always will be the children heaven and hell made together.

But as Fairyland had to grow to inhabit a full series rather than a single novel, it had to become as big and real as our own world. It needed an underworld of its own. September’s shadow had disappeared under the river Barleybroom and at the moment it did, I knew that if by some lucky chance I got to write a sequel, that’s where I would go, deep into the dark world beneath Fairyland, where September could meet her Erishkegal. Where everything she knows could become its opposite and the wild magic of Fairyland could have free reign. Where she could begin her slow journey toward adulthood—which is also what underworld stories and portal fantasies are about. The first Fairyland novel was about attempts to impose order on the numinous and the wonderful. The second is about chaos getting its revenge on that order. The two books are in a very real sense mirror images of one another. Everything comforting is turned on its head; everything frightening is not at all what it seems.

Or else what’s a sequel all about?

There’s a scene early in Revels in which September visits a Sibyl on her way to the underworld. (Naturally, every underworld needs a Sibyl.) They have tea and discuss the nature of heroes, the universe, and job aptitude, as you do when you’re thirteen and have no idea what you want to be when you grow up. As September turns away to enter Fairyland-Below, she asks the Sibyl a question: “Sibyl, what do you want?”

The Sibyl, who loves her job and her solitude and her world, answers: “I want to live.”

In the end, this simple exchange is what the Fairyland novels are all about. Children will see in the passage a conversation about work and grownup life that is not about drudgery or the loss of magic, an affirmation of the great and powerful desire to live as you want to live, the longing to keep on living even when that living is dark and hard, a theme that plays loud and clear all through Revels. Adults may recognize the echo of The Wasteland, and in turn The Satyricon, the source from which T.S. Eliot took his quote: The boys asked her: Sibyl, what do you want? And the Sibyl answered: I want to die. And as those child readers grow up and reread that funny novel with the purple cover, they will see both.

Fairyland begins in folklore, in myth, in the narratives we keep telling, compulsively, over and over again. A child goes to a magical country. A wicked despot is brought down. A girl goes into the underworld and comes out again. But many of the narratives we tell over and over are pretty problematic. They exclude or punish girls and women, they enforce ugly ideas about adulthood and relationships, they tell kids that unless they look and think a certain way, they are fated to fail. Fairyland tries to turn those narratives on their heads, to present another way of behaving in a fantasy story, to include and yes, to uplift, without being schmaltzy—because to uplift yourself or others, to keep your humor and happiness, is actually incredibly hard work. I have tried to write stories that go into the underworld of myth and bring out life and fire—where the old world looked at a woman alone and immortal and said: she must long to die, I have tried to say: look at her live!

So come with me, back to Fairyland. Meet me in the underworld.

I’ve kept the light on for you.

[A note: Tor.com is giving away copies of the book here.]

Catherynne M. Valente, acclaimed author of many books for adults, made her children’s book debut with The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making. She lives on an island off the coast of Maine with her husband.